.png)

In recognition of our incredible partnering farmers, we reflected on the policies that created the agricultural system we rely on today to better understand how to improve the system for tomorrow. As we look to our policy-makers to help cultivate a more equitable and sustainable food system, it is important to note the policies that have produced the modern food system. The history of agricultural policy in America is not entirely a linear progression towards improvement—certain policies have inhibited farmers from providing enough food supply to meet the demand, while other policies have increased their revenue through government subsidies, but created surpluses that go to waste. To determine how agriculture policy has changed over time, we examined the policies throughout American history that have had the greatest impact on the farmers that we know and love.

A Brief Timeline of American Agriculture Policy

.jpg)

Balanced Crop Valuation and Limited Production

In an attempt to aid farmers after the Great Depression, Congress passed the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA), limiting the amount of produce each farmer could grow as means of regulating crop values through supply and demand. Surpluses of corn, cotton, milk, peanuts, rice, tobacco, and wheat had resulted in very low market prices, devastating farming communities. The reduction of supply brought crop values, and thus consumer prices, back up, and farmers who agreed to these restrictions were given federal subsidies. While reducing the supply raised crop values, helping farmers financially, it also raised prices for the consumer. As a result of these higher prices and limited supply, food became inaccessible to many Americans.

The Shift Towards Overproduction

A few decades later, the federal government implemented a series of policy changes in an attempt to remedy this food shortage and make food more accessible for all. The 1970’s agriculture policies and Green Revolution, which expanded the use of chemical fertilizers to increase supply, overcorrected this issue, shifting farming culture towards an era of imbalanced supply and demand by rewarding overproduction, as opposed to the previously-rewarded restricted production. Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz envisioned a centralized food system that rewarded overproduction to decrease the cost of food, thereby making food available to those who could not previously afford it. While this did expand food accessibility to many Americans, the legacy of Earl Butz’s time in office and this shift towards overproduction devastated small farmers and led to the rise of the factory farms, which grew fewer crop varieties in much higher quantities. This imbalance of supply and demand has caused negative impacts on the environment, small farmers, and the sustainability of this system of surplus.

Beginning with the Food Security Act of 1985, agricultural policy further shifted to a system of government incentives and subsidies for farmers; however, not all farmers receive these income supplements. Early-2000s policies, such as The 2002 Farm Security and Rural Investment Act, further expanded farming subsidies, which lifted many farmers out of poverty, but also encouraged them to grow as much produce as possible. Most of these government subsidies went (and still go) to animal feed like corn to encourage meat production, as well as cotton, wheat and rice, perpetuating a culture of surplus for these goods while fruit and vegetable farmers could not rely on the government for assistance.

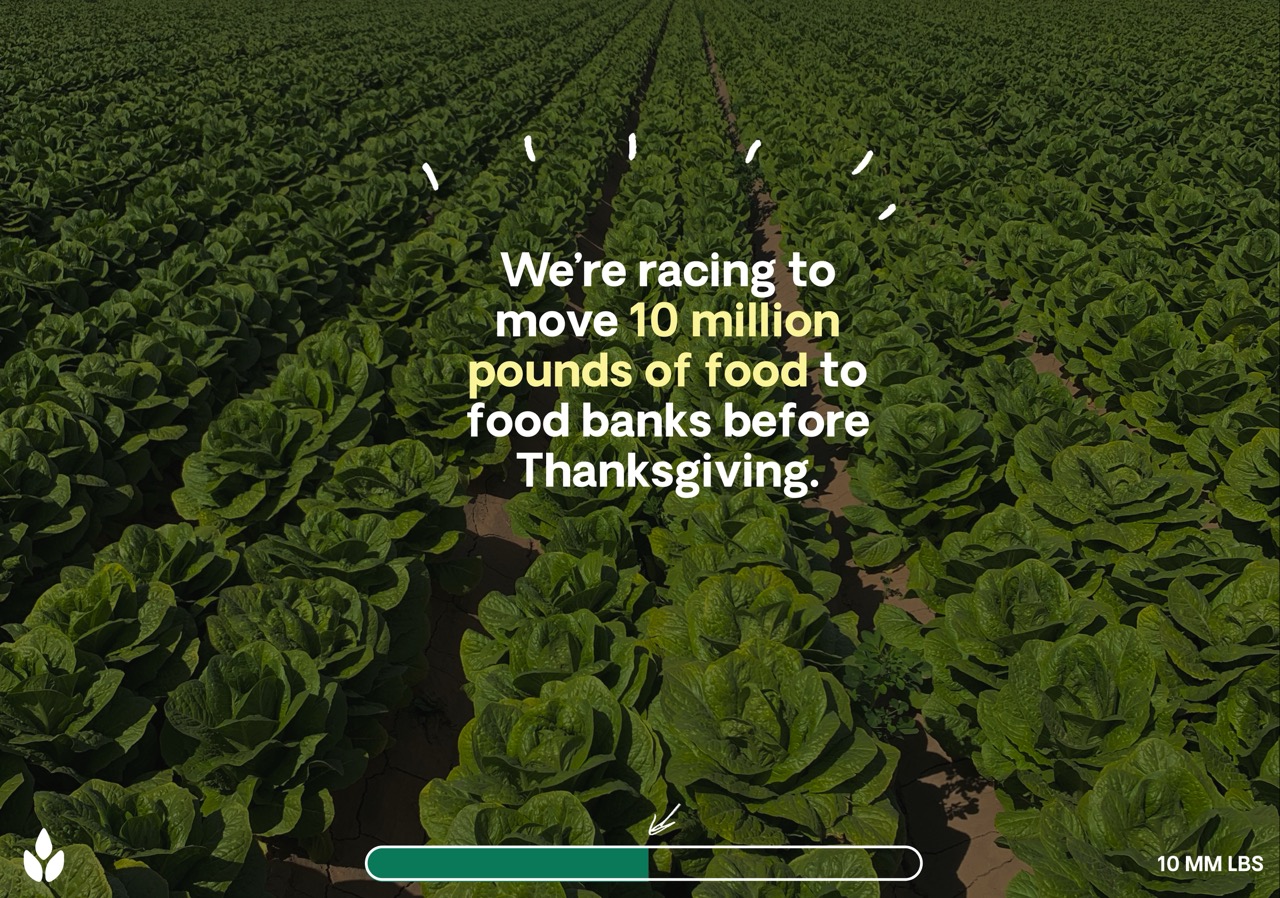

The Modern Agricultural Industry: A System of Surplus

For nearly the first time in history, fruit and vegetable farmers have seen unimaginable amounts of surplus during the COVID-19 pandemic as restaurants and other large-scale buyers have shut down. That’s why The Farmlink Project was created—to aid those farmers and prevent them from throwing out their surplus produce. However, our work at The Farmlink Project treats only the symptoms of this system of surplus. Our goal is for this work to become obsolete in the future, and the only way that can happen is through policy changes to curtail the overproduction that plagues the modern food system and to create a more streamlined supply chain so that surplus food goes directly to those who need it. New policies will ideally offer support for small family-owned or minority-owned farms, as well as incentivize crops that are both nutritious and have small environmental impacts. A shift away from large-scale meat production and commodity crops will not only help the planet, but also aid small farmers and minimize food waste.

.png)

A Look Towards the Future

With the new presidential administration will come new agricultural policy. President Biden has made a number of promises to help farmers, which, if enacted properly, will aid a number of the farmers that The Farmlink Project is proud to work alongside. To learn more about Biden’s new policies and the farmers that they will aid, check out this article about President Biden’s Plans for the American Food System.

< Back

.png)

In recognition of our incredible partnering farmers, we reflected on the policies that created the agricultural system we rely on today to better understand how to improve the system for tomorrow. As we look to our policy-makers to help cultivate a more equitable and sustainable food system, it is important to note the policies that have produced the modern food system. The history of agricultural policy in America is not entirely a linear progression towards improvement—certain policies have inhibited farmers from providing enough food supply to meet the demand, while other policies have increased their revenue through government subsidies, but created surpluses that go to waste. To determine how agriculture policy has changed over time, we examined the policies throughout American history that have had the greatest impact on the farmers that we know and love.

A Brief Timeline of American Agriculture Policy

.jpg)

Balanced Crop Valuation and Limited Production

In an attempt to aid farmers after the Great Depression, Congress passed the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA), limiting the amount of produce each farmer could grow as means of regulating crop values through supply and demand. Surpluses of corn, cotton, milk, peanuts, rice, tobacco, and wheat had resulted in very low market prices, devastating farming communities. The reduction of supply brought crop values, and thus consumer prices, back up, and farmers who agreed to these restrictions were given federal subsidies. While reducing the supply raised crop values, helping farmers financially, it also raised prices for the consumer. As a result of these higher prices and limited supply, food became inaccessible to many Americans.

The Shift Towards Overproduction

A few decades later, the federal government implemented a series of policy changes in an attempt to remedy this food shortage and make food more accessible for all. The 1970’s agriculture policies and Green Revolution, which expanded the use of chemical fertilizers to increase supply, overcorrected this issue, shifting farming culture towards an era of imbalanced supply and demand by rewarding overproduction, as opposed to the previously-rewarded restricted production. Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz envisioned a centralized food system that rewarded overproduction to decrease the cost of food, thereby making food available to those who could not previously afford it. While this did expand food accessibility to many Americans, the legacy of Earl Butz’s time in office and this shift towards overproduction devastated small farmers and led to the rise of the factory farms, which grew fewer crop varieties in much higher quantities. This imbalance of supply and demand has caused negative impacts on the environment, small farmers, and the sustainability of this system of surplus.

Beginning with the Food Security Act of 1985, agricultural policy further shifted to a system of government incentives and subsidies for farmers; however, not all farmers receive these income supplements. Early-2000s policies, such as The 2002 Farm Security and Rural Investment Act, further expanded farming subsidies, which lifted many farmers out of poverty, but also encouraged them to grow as much produce as possible. Most of these government subsidies went (and still go) to animal feed like corn to encourage meat production, as well as cotton, wheat and rice, perpetuating a culture of surplus for these goods while fruit and vegetable farmers could not rely on the government for assistance.

The Modern Agricultural Industry: A System of Surplus

For nearly the first time in history, fruit and vegetable farmers have seen unimaginable amounts of surplus during the COVID-19 pandemic as restaurants and other large-scale buyers have shut down. That’s why The Farmlink Project was created—to aid those farmers and prevent them from throwing out their surplus produce. However, our work at The Farmlink Project treats only the symptoms of this system of surplus. Our goal is for this work to become obsolete in the future, and the only way that can happen is through policy changes to curtail the overproduction that plagues the modern food system and to create a more streamlined supply chain so that surplus food goes directly to those who need it. New policies will ideally offer support for small family-owned or minority-owned farms, as well as incentivize crops that are both nutritious and have small environmental impacts. A shift away from large-scale meat production and commodity crops will not only help the planet, but also aid small farmers and minimize food waste.

.png)

A Look Towards the Future

With the new presidential administration will come new agricultural policy. President Biden has made a number of promises to help farmers, which, if enacted properly, will aid a number of the farmers that The Farmlink Project is proud to work alongside. To learn more about Biden’s new policies and the farmers that they will aid, check out this article about President Biden’s Plans for the American Food System.

A Dive Into Agriculture Policy

.png)

In recognition of our incredible partnering farmers, we reflected on the policies that created the agricultural system we rely on today to better understand how to improve the system for tomorrow. As we look to our policy-makers to help cultivate a more equitable and sustainable food system, it is important to note the policies that have produced the modern food system. The history of agricultural policy in America is not entirely a linear progression towards improvement—certain policies have inhibited farmers from providing enough food supply to meet the demand, while other policies have increased their revenue through government subsidies, but created surpluses that go to waste. To determine how agriculture policy has changed over time, we examined the policies throughout American history that have had the greatest impact on the farmers that we know and love.

A Brief Timeline of American Agriculture Policy

.jpg)

Balanced Crop Valuation and Limited Production

In an attempt to aid farmers after the Great Depression, Congress passed the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA), limiting the amount of produce each farmer could grow as means of regulating crop values through supply and demand. Surpluses of corn, cotton, milk, peanuts, rice, tobacco, and wheat had resulted in very low market prices, devastating farming communities. The reduction of supply brought crop values, and thus consumer prices, back up, and farmers who agreed to these restrictions were given federal subsidies. While reducing the supply raised crop values, helping farmers financially, it also raised prices for the consumer. As a result of these higher prices and limited supply, food became inaccessible to many Americans.

The Shift Towards Overproduction

A few decades later, the federal government implemented a series of policy changes in an attempt to remedy this food shortage and make food more accessible for all. The 1970’s agriculture policies and Green Revolution, which expanded the use of chemical fertilizers to increase supply, overcorrected this issue, shifting farming culture towards an era of imbalanced supply and demand by rewarding overproduction, as opposed to the previously-rewarded restricted production. Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz envisioned a centralized food system that rewarded overproduction to decrease the cost of food, thereby making food available to those who could not previously afford it. While this did expand food accessibility to many Americans, the legacy of Earl Butz’s time in office and this shift towards overproduction devastated small farmers and led to the rise of the factory farms, which grew fewer crop varieties in much higher quantities. This imbalance of supply and demand has caused negative impacts on the environment, small farmers, and the sustainability of this system of surplus.

Beginning with the Food Security Act of 1985, agricultural policy further shifted to a system of government incentives and subsidies for farmers; however, not all farmers receive these income supplements. Early-2000s policies, such as The 2002 Farm Security and Rural Investment Act, further expanded farming subsidies, which lifted many farmers out of poverty, but also encouraged them to grow as much produce as possible. Most of these government subsidies went (and still go) to animal feed like corn to encourage meat production, as well as cotton, wheat and rice, perpetuating a culture of surplus for these goods while fruit and vegetable farmers could not rely on the government for assistance.

The Modern Agricultural Industry: A System of Surplus

For nearly the first time in history, fruit and vegetable farmers have seen unimaginable amounts of surplus during the COVID-19 pandemic as restaurants and other large-scale buyers have shut down. That’s why The Farmlink Project was created—to aid those farmers and prevent them from throwing out their surplus produce. However, our work at The Farmlink Project treats only the symptoms of this system of surplus. Our goal is for this work to become obsolete in the future, and the only way that can happen is through policy changes to curtail the overproduction that plagues the modern food system and to create a more streamlined supply chain so that surplus food goes directly to those who need it. New policies will ideally offer support for small family-owned or minority-owned farms, as well as incentivize crops that are both nutritious and have small environmental impacts. A shift away from large-scale meat production and commodity crops will not only help the planet, but also aid small farmers and minimize food waste.

.png)

A Look Towards the Future

With the new presidential administration will come new agricultural policy. President Biden has made a number of promises to help farmers, which, if enacted properly, will aid a number of the farmers that The Farmlink Project is proud to work alongside. To learn more about Biden’s new policies and the farmers that they will aid, check out this article about President Biden’s Plans for the American Food System.

.png)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)