“When you have, you give.” That’s the motto that Brette Waters, Executive Director (and only employee) of Chefs to End Hunger, lives her life by. And boy, does she give. When it comes to the internal operations of Chefs to End Hunger, Brette Waters does it all. She is her own logistics director, data and analytics manager, marketing team, donor coordinator and partnership supervisor. She oversees the reallocation of prepared food from restaurants and hotels to charitable organizations that distribute the food to those in need. Chefs to End Hunger was created by the Vesta Foodservice company, a major food supplier that already had existing supply chains in place to facilitate redistribution of surplus. Places like restaurants and hotels can request containers to package their excess food, and Vesta will provide the logistics to pick up and distribute the surplus to partnering community organizations.

Growing up in Stockton, California, about an hour east of San Francisco, Brette was raised to believe she should help people whenever possible. In her community, she saw extreme wealth disparities that made an early impression. She recounted visiting San Francisco as a child and being devastated by the inequalities that she saw, regularly asking her father to save their dinner leftovers to give to the homeless population. Brette recalled thinking, “I can’t give them the jacket off my back, but I can give them my food.”

A lifelong career in the food service industry—attending culinary school and working as a waitress, as a bartender, and in farmers markets—prepared Brette for the opportunity to direct Chefs to End Hunger when the nonprofit was founded. She was already working for Vesta Foodservice, and it seemed like a natural fit to lead this new organization. She had learned early on that communication and PR were her strongest skills, and since she was young, Brette has felt compelled to use those skills to contribute to a meaningful project. So, when the opportunity to direct a nonprofit that was addressing a problem near and dear to her heart came along, she jumped at the opportunity to use her strengths to feed as many people as possible.

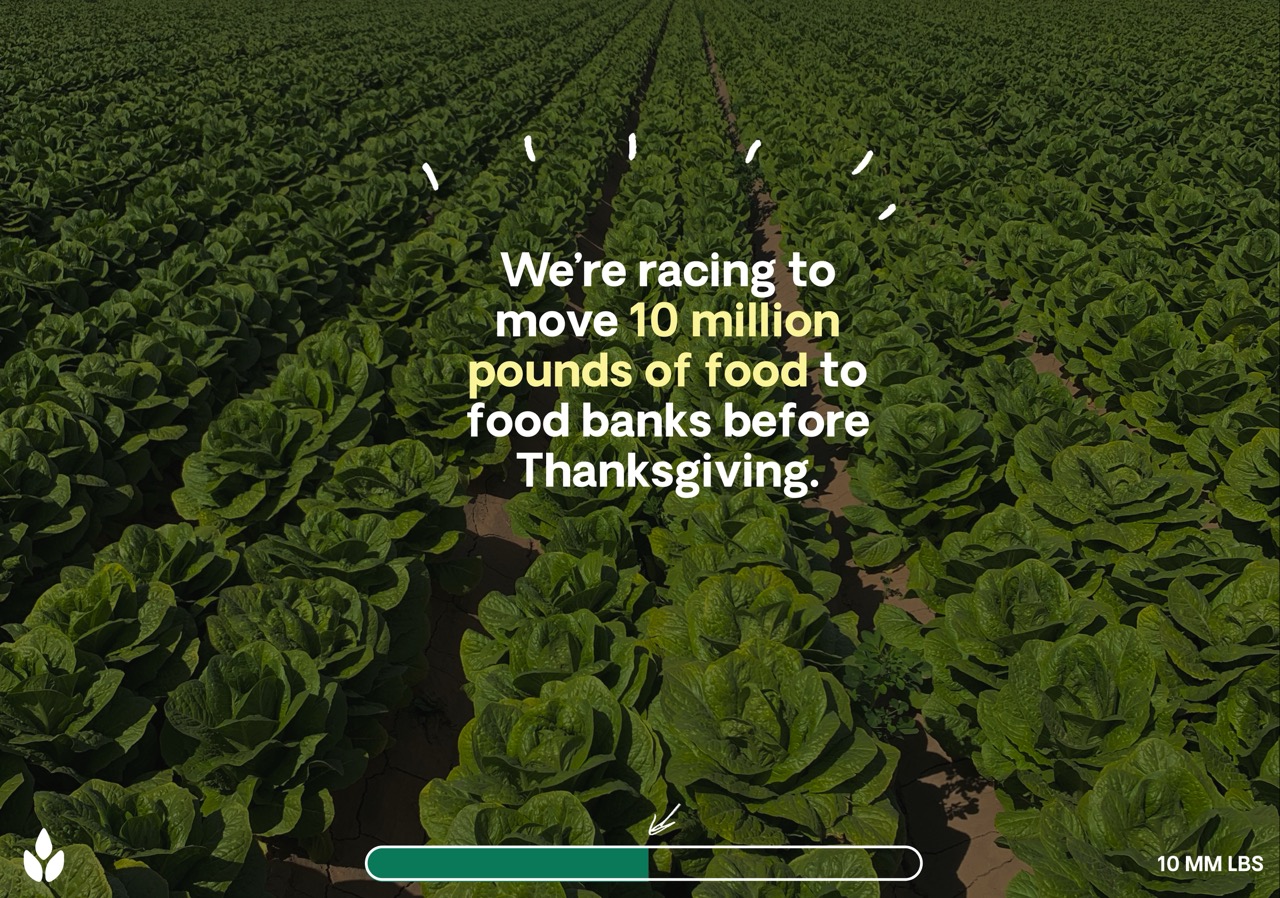

In 2019, Chefs to End Hunger recovered 4.25 million pounds of food, providing 3.5 million meals to people in need. The organization had lots of momentum that came to a screeching halt with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. This massive disruption to the food supply chain forced Brette to shift her focus. With restaurants and hotels significantly reducing their operations, Chefs to End Hunger’s main sources of surplus were greatly diminished. But Brette knew that their mission was too important to quit; so, she sought out surplus from different sources. USDA’s Farmers to Families food box program provided a framework for Chefs to End Hunger to continue to address food insecurity. Working to provide boxes to hungry people sparked a light-bulb moment for Brette—she realized that as the person in charge of Chefs to End Hunger, she had the power to choose to whom she wanted to provide food. Brette acknowledged that she wanted to be intentional with her food recovery by providing food to the people who are often overlooked in the government-run food system.

With a new energy, in the middle of 2020, Brette began focusing on moving food to marginalized communities—BIPOC, LGBTQ+, undocumented restaurant workers, and others who are regularly underrepresented and thus see higher rates of food insecurity. To achieve this goal, Brette prioritized partnerships with organizations working towards similar goals like The Farmlink Project and No Us Without You, an LA-based nonprofit working to provide food security for undocumented workers in the hospitality industry.

In addition to being a powerhouse businesswoman, Brette is also raising her three adorable daughters. Her eleven-year-old, Ava, has already discovered a passion for the ocean, and Brette beamed with pride as she told me that Ava is raising money for her favorite charity by sorting her recyclables at home and preventing plastic waste from entering the ocean. Instilling the belief that small efforts can make a massive difference is critical to Brette’s parenting style and is as important to her as getting good grades or excelling in extracurriculars.

Brette has lots of big plans for the future. Ideally, she would love to see the cooperation of businesses, farmers, the government, and students to continue to address the problem of food insecurity. She passionately believes that there is plenty of existing infrastructure that can easily be leveraged to distribute food if businesses and transportation companies are willing to pivot to a slightly different business model. She wants to encourage farmers to create metrics to efficiently move their surplus out of the fields and be proactive about reaching out to food rescue organizations. Brette also believes that students and young people are the untapped resource in addressing these issues and wants to empower the youth to speak up and share their ideas. The intersection of these many groups is critical to solving the hunger crisis, and Brette is working every day to do her part.

< Back

“When you have, you give.” That’s the motto that Brette Waters, Executive Director (and only employee) of Chefs to End Hunger, lives her life by. And boy, does she give. When it comes to the internal operations of Chefs to End Hunger, Brette Waters does it all. She is her own logistics director, data and analytics manager, marketing team, donor coordinator and partnership supervisor. She oversees the reallocation of prepared food from restaurants and hotels to charitable organizations that distribute the food to those in need. Chefs to End Hunger was created by the Vesta Foodservice company, a major food supplier that already had existing supply chains in place to facilitate redistribution of surplus. Places like restaurants and hotels can request containers to package their excess food, and Vesta will provide the logistics to pick up and distribute the surplus to partnering community organizations.

Growing up in Stockton, California, about an hour east of San Francisco, Brette was raised to believe she should help people whenever possible. In her community, she saw extreme wealth disparities that made an early impression. She recounted visiting San Francisco as a child and being devastated by the inequalities that she saw, regularly asking her father to save their dinner leftovers to give to the homeless population. Brette recalled thinking, “I can’t give them the jacket off my back, but I can give them my food.”

A lifelong career in the food service industry—attending culinary school and working as a waitress, as a bartender, and in farmers markets—prepared Brette for the opportunity to direct Chefs to End Hunger when the nonprofit was founded. She was already working for Vesta Foodservice, and it seemed like a natural fit to lead this new organization. She had learned early on that communication and PR were her strongest skills, and since she was young, Brette has felt compelled to use those skills to contribute to a meaningful project. So, when the opportunity to direct a nonprofit that was addressing a problem near and dear to her heart came along, she jumped at the opportunity to use her strengths to feed as many people as possible.

In 2019, Chefs to End Hunger recovered 4.25 million pounds of food, providing 3.5 million meals to people in need. The organization had lots of momentum that came to a screeching halt with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. This massive disruption to the food supply chain forced Brette to shift her focus. With restaurants and hotels significantly reducing their operations, Chefs to End Hunger’s main sources of surplus were greatly diminished. But Brette knew that their mission was too important to quit; so, she sought out surplus from different sources. USDA’s Farmers to Families food box program provided a framework for Chefs to End Hunger to continue to address food insecurity. Working to provide boxes to hungry people sparked a light-bulb moment for Brette—she realized that as the person in charge of Chefs to End Hunger, she had the power to choose to whom she wanted to provide food. Brette acknowledged that she wanted to be intentional with her food recovery by providing food to the people who are often overlooked in the government-run food system.

With a new energy, in the middle of 2020, Brette began focusing on moving food to marginalized communities—BIPOC, LGBTQ+, undocumented restaurant workers, and others who are regularly underrepresented and thus see higher rates of food insecurity. To achieve this goal, Brette prioritized partnerships with organizations working towards similar goals like The Farmlink Project and No Us Without You, an LA-based nonprofit working to provide food security for undocumented workers in the hospitality industry.

In addition to being a powerhouse businesswoman, Brette is also raising her three adorable daughters. Her eleven-year-old, Ava, has already discovered a passion for the ocean, and Brette beamed with pride as she told me that Ava is raising money for her favorite charity by sorting her recyclables at home and preventing plastic waste from entering the ocean. Instilling the belief that small efforts can make a massive difference is critical to Brette’s parenting style and is as important to her as getting good grades or excelling in extracurriculars.

Brette has lots of big plans for the future. Ideally, she would love to see the cooperation of businesses, farmers, the government, and students to continue to address the problem of food insecurity. She passionately believes that there is plenty of existing infrastructure that can easily be leveraged to distribute food if businesses and transportation companies are willing to pivot to a slightly different business model. She wants to encourage farmers to create metrics to efficiently move their surplus out of the fields and be proactive about reaching out to food rescue organizations. Brette also believes that students and young people are the untapped resource in addressing these issues and wants to empower the youth to speak up and share their ideas. The intersection of these many groups is critical to solving the hunger crisis, and Brette is working every day to do her part.

Brette Waters

Executive Director of Chefs to End Hunger

“When you have, you give.” That’s the motto that Brette Waters, Executive Director (and only employee) of Chefs to End Hunger, lives her life by. And boy, does she give. When it comes to the internal operations of Chefs to End Hunger, Brette Waters does it all. She is her own logistics director, data and analytics manager, marketing team, donor coordinator and partnership supervisor. She oversees the reallocation of prepared food from restaurants and hotels to charitable organizations that distribute the food to those in need. Chefs to End Hunger was created by the Vesta Foodservice company, a major food supplier that already had existing supply chains in place to facilitate redistribution of surplus. Places like restaurants and hotels can request containers to package their excess food, and Vesta will provide the logistics to pick up and distribute the surplus to partnering community organizations.

Growing up in Stockton, California, about an hour east of San Francisco, Brette was raised to believe she should help people whenever possible. In her community, she saw extreme wealth disparities that made an early impression. She recounted visiting San Francisco as a child and being devastated by the inequalities that she saw, regularly asking her father to save their dinner leftovers to give to the homeless population. Brette recalled thinking, “I can’t give them the jacket off my back, but I can give them my food.”

A lifelong career in the food service industry—attending culinary school and working as a waitress, as a bartender, and in farmers markets—prepared Brette for the opportunity to direct Chefs to End Hunger when the nonprofit was founded. She was already working for Vesta Foodservice, and it seemed like a natural fit to lead this new organization. She had learned early on that communication and PR were her strongest skills, and since she was young, Brette has felt compelled to use those skills to contribute to a meaningful project. So, when the opportunity to direct a nonprofit that was addressing a problem near and dear to her heart came along, she jumped at the opportunity to use her strengths to feed as many people as possible.

In 2019, Chefs to End Hunger recovered 4.25 million pounds of food, providing 3.5 million meals to people in need. The organization had lots of momentum that came to a screeching halt with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. This massive disruption to the food supply chain forced Brette to shift her focus. With restaurants and hotels significantly reducing their operations, Chefs to End Hunger’s main sources of surplus were greatly diminished. But Brette knew that their mission was too important to quit; so, she sought out surplus from different sources. USDA’s Farmers to Families food box program provided a framework for Chefs to End Hunger to continue to address food insecurity. Working to provide boxes to hungry people sparked a light-bulb moment for Brette—she realized that as the person in charge of Chefs to End Hunger, she had the power to choose to whom she wanted to provide food. Brette acknowledged that she wanted to be intentional with her food recovery by providing food to the people who are often overlooked in the government-run food system.

With a new energy, in the middle of 2020, Brette began focusing on moving food to marginalized communities—BIPOC, LGBTQ+, undocumented restaurant workers, and others who are regularly underrepresented and thus see higher rates of food insecurity. To achieve this goal, Brette prioritized partnerships with organizations working towards similar goals like The Farmlink Project and No Us Without You, an LA-based nonprofit working to provide food security for undocumented workers in the hospitality industry.

In addition to being a powerhouse businesswoman, Brette is also raising her three adorable daughters. Her eleven-year-old, Ava, has already discovered a passion for the ocean, and Brette beamed with pride as she told me that Ava is raising money for her favorite charity by sorting her recyclables at home and preventing plastic waste from entering the ocean. Instilling the belief that small efforts can make a massive difference is critical to Brette’s parenting style and is as important to her as getting good grades or excelling in extracurriculars.

Brette has lots of big plans for the future. Ideally, she would love to see the cooperation of businesses, farmers, the government, and students to continue to address the problem of food insecurity. She passionately believes that there is plenty of existing infrastructure that can easily be leveraged to distribute food if businesses and transportation companies are willing to pivot to a slightly different business model. She wants to encourage farmers to create metrics to efficiently move their surplus out of the fields and be proactive about reaching out to food rescue organizations. Brette also believes that students and young people are the untapped resource in addressing these issues and wants to empower the youth to speak up and share their ideas. The intersection of these many groups is critical to solving the hunger crisis, and Brette is working every day to do her part.

.png)

.jpg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)