Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the San Antonio Food Bank served almost 60,000 food-insecure individuals each week. Founded in 1980 as part of the Feeding America nationwide network of food banks, the organization now serves Southwest Texas with a mission to fight hunger and guide clients to self-sufficiency through food distribution programs, education, and advocacy. Their partner agencies span 16 counties, distributing perishable and non-perishable food items to children, families, seniors, and individuals in need.

After reading about the risk of COVID-19 in February 2020, the organization sprung into action, launching a preparedness and prevention campaign to assist seniors already receiving meal and grocery deliveries.

“We were supplying seniors with hand sanitizer, cleaning products, education, and then stocking them up, thinking we wouldn’t be able to get to them if we were quarantined,” said CEO Eric Cooper. “But in no way did it sink in that that would actually happen."

By the end of March 2020, however, demand at the San Antonio Food Bank had doubled from 60,000 to 120,000 people a week.

.jpeg)

As the pandemic began to unravel the economy and disrupt the food supply chain, demand doubling and supply decreasing put the Food Bank in a vulnerable place, emptying their inventory faster than they could restock. Excess food that restaurants, hotels, and caterers had previously donated to the Food Bank was no longer available. A previously-reliable supply of corporate volunteer groups, which made up a significant portion of their 1,000 weekly volunteers, dried up as companies passed rules against any in-person group activities. Many food pantries that the Food Bank partnered with to distribute donations were forced to close to protect the health of their elderly workers.

But the San Antonio Food Bank found creative ways to change operations to meet surging demand. “A lot of our distributions moved to a strategy we’ve always done, basically, direct distributions to clients in parking lots. That activity in the COVID-19 environment under CDC protocols was actually a fairly effective way to get families groceries,” said Eric. In addition to curbside distributions and pickup, home-delivered grocery boxes and meals became a top priority, peaking at around 7,000 home deliveries each month.

.jpeg)

This February, Texas was devastated by the coldest winter storm it had experienced in over 30 years. Frozen pipes burst and indoor temperatures in homes quickly dropped to freezing after heat systems failed, resulting in a public health disaster. After an already trying year, the Food Bank never faltered in its commitment to serve the communities of Southwest Texas.

Because people had no power or water for cooking, operations shifted from grocery deliveries to premade meals. “We never closed,” said Eric. “I had chefs sleeping in the kitchen and working off of a generator.”

Utilizing their stored inventory of food, they started emptying their warehouse to get meals to families, providing food to about 70,000 people the first weekend after the storms. The Food Bank also supplied tens of thousands of meals to the hotels where families were staying after being forced to evacuate their homes. Many of the volunteers who came out to help distribute food, Eric noted, didn’t have power and water in their own houses.

.jpeg)

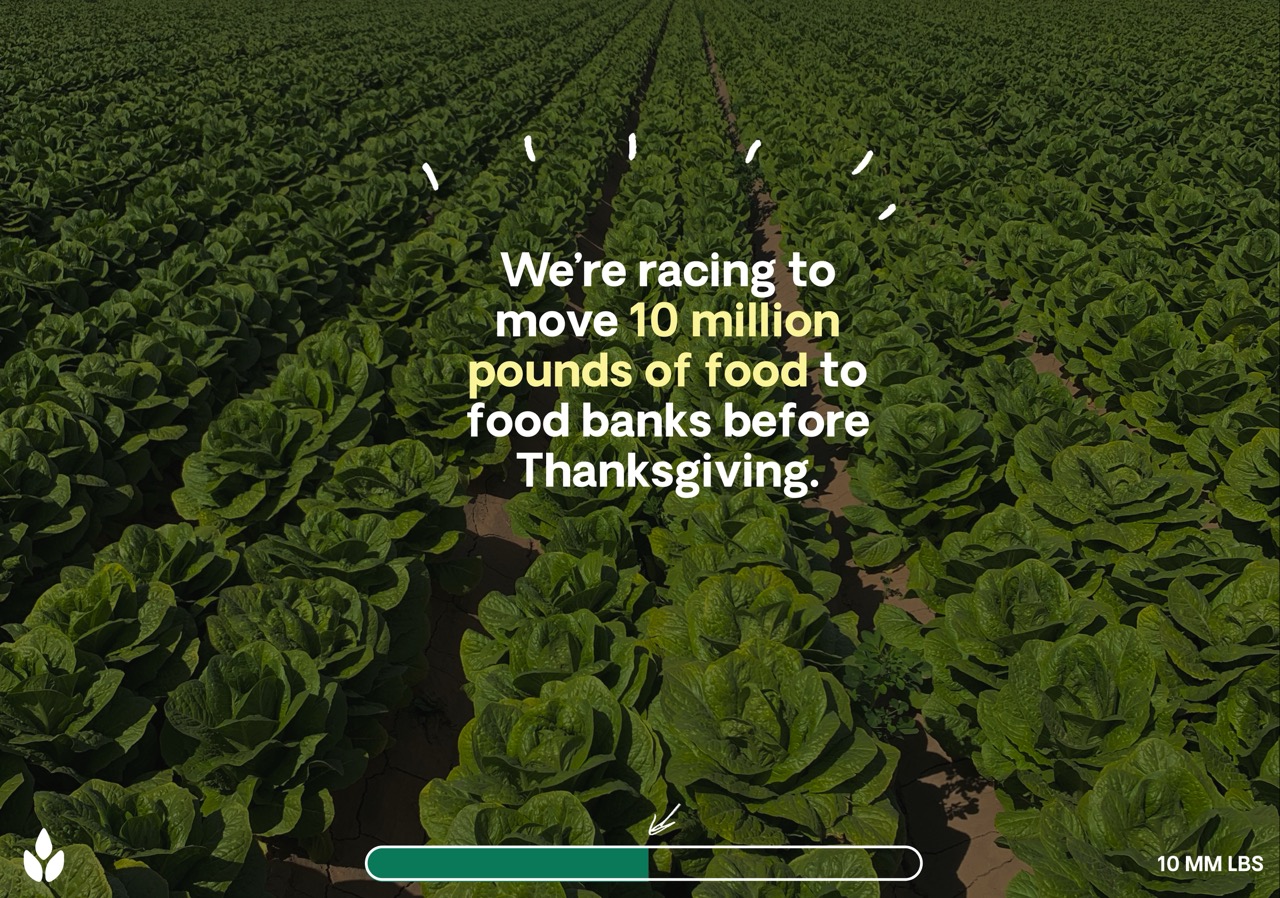

After delivering potatoes to the San Antonio Food Bank in June 2020, The Farmlink Project has since facilitated deliveries of over 67,000 pounds of mixed greens to the Food Bank in February and March from Taylor Farms in Laredo, Texas.

Despite a tumultuous year, San Antonio Food Bank has responded to crisis after crisis, never wavering from their goal to take a holistic approach to fighting food insecurity and guiding clients to health and self-sufficiency.

“If we’re going to work our way out of the job, it can’t just be about feeding the line. You have to be working to shorten the line,” said Eric. “We fight the daily disaster of poverty, but when a natural disaster occurs, we step up to that too.”

.jpeg)

If you’d like to learn more about San Antonio Food Bank, check out their website here!

If you live in the area and would like to volunteer with the organization, click here.

< Back

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the San Antonio Food Bank served almost 60,000 food-insecure individuals each week. Founded in 1980 as part of the Feeding America nationwide network of food banks, the organization now serves Southwest Texas with a mission to fight hunger and guide clients to self-sufficiency through food distribution programs, education, and advocacy. Their partner agencies span 16 counties, distributing perishable and non-perishable food items to children, families, seniors, and individuals in need.

After reading about the risk of COVID-19 in February 2020, the organization sprung into action, launching a preparedness and prevention campaign to assist seniors already receiving meal and grocery deliveries.

“We were supplying seniors with hand sanitizer, cleaning products, education, and then stocking them up, thinking we wouldn’t be able to get to them if we were quarantined,” said CEO Eric Cooper. “But in no way did it sink in that that would actually happen."

By the end of March 2020, however, demand at the San Antonio Food Bank had doubled from 60,000 to 120,000 people a week.

.jpeg)

As the pandemic began to unravel the economy and disrupt the food supply chain, demand doubling and supply decreasing put the Food Bank in a vulnerable place, emptying their inventory faster than they could restock. Excess food that restaurants, hotels, and caterers had previously donated to the Food Bank was no longer available. A previously-reliable supply of corporate volunteer groups, which made up a significant portion of their 1,000 weekly volunteers, dried up as companies passed rules against any in-person group activities. Many food pantries that the Food Bank partnered with to distribute donations were forced to close to protect the health of their elderly workers.

But the San Antonio Food Bank found creative ways to change operations to meet surging demand. “A lot of our distributions moved to a strategy we’ve always done, basically, direct distributions to clients in parking lots. That activity in the COVID-19 environment under CDC protocols was actually a fairly effective way to get families groceries,” said Eric. In addition to curbside distributions and pickup, home-delivered grocery boxes and meals became a top priority, peaking at around 7,000 home deliveries each month.

.jpeg)

This February, Texas was devastated by the coldest winter storm it had experienced in over 30 years. Frozen pipes burst and indoor temperatures in homes quickly dropped to freezing after heat systems failed, resulting in a public health disaster. After an already trying year, the Food Bank never faltered in its commitment to serve the communities of Southwest Texas.

Because people had no power or water for cooking, operations shifted from grocery deliveries to premade meals. “We never closed,” said Eric. “I had chefs sleeping in the kitchen and working off of a generator.”

Utilizing their stored inventory of food, they started emptying their warehouse to get meals to families, providing food to about 70,000 people the first weekend after the storms. The Food Bank also supplied tens of thousands of meals to the hotels where families were staying after being forced to evacuate their homes. Many of the volunteers who came out to help distribute food, Eric noted, didn’t have power and water in their own houses.

.jpeg)

After delivering potatoes to the San Antonio Food Bank in June 2020, The Farmlink Project has since facilitated deliveries of over 67,000 pounds of mixed greens to the Food Bank in February and March from Taylor Farms in Laredo, Texas.

Despite a tumultuous year, San Antonio Food Bank has responded to crisis after crisis, never wavering from their goal to take a holistic approach to fighting food insecurity and guiding clients to health and self-sufficiency.

“If we’re going to work our way out of the job, it can’t just be about feeding the line. You have to be working to shorten the line,” said Eric. “We fight the daily disaster of poverty, but when a natural disaster occurs, we step up to that too.”

.jpeg)

If you’d like to learn more about San Antonio Food Bank, check out their website here!

If you live in the area and would like to volunteer with the organization, click here.

San Antonio Food Bank Braves Natural Disasters to Serve Record Numbers of Texans

San Antonio, TX

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the San Antonio Food Bank served almost 60,000 food-insecure individuals each week. Founded in 1980 as part of the Feeding America nationwide network of food banks, the organization now serves Southwest Texas with a mission to fight hunger and guide clients to self-sufficiency through food distribution programs, education, and advocacy. Their partner agencies span 16 counties, distributing perishable and non-perishable food items to children, families, seniors, and individuals in need.

After reading about the risk of COVID-19 in February 2020, the organization sprung into action, launching a preparedness and prevention campaign to assist seniors already receiving meal and grocery deliveries.

“We were supplying seniors with hand sanitizer, cleaning products, education, and then stocking them up, thinking we wouldn’t be able to get to them if we were quarantined,” said CEO Eric Cooper. “But in no way did it sink in that that would actually happen."

By the end of March 2020, however, demand at the San Antonio Food Bank had doubled from 60,000 to 120,000 people a week.

.jpeg)

As the pandemic began to unravel the economy and disrupt the food supply chain, demand doubling and supply decreasing put the Food Bank in a vulnerable place, emptying their inventory faster than they could restock. Excess food that restaurants, hotels, and caterers had previously donated to the Food Bank was no longer available. A previously-reliable supply of corporate volunteer groups, which made up a significant portion of their 1,000 weekly volunteers, dried up as companies passed rules against any in-person group activities. Many food pantries that the Food Bank partnered with to distribute donations were forced to close to protect the health of their elderly workers.

But the San Antonio Food Bank found creative ways to change operations to meet surging demand. “A lot of our distributions moved to a strategy we’ve always done, basically, direct distributions to clients in parking lots. That activity in the COVID-19 environment under CDC protocols was actually a fairly effective way to get families groceries,” said Eric. In addition to curbside distributions and pickup, home-delivered grocery boxes and meals became a top priority, peaking at around 7,000 home deliveries each month.

.jpeg)

This February, Texas was devastated by the coldest winter storm it had experienced in over 30 years. Frozen pipes burst and indoor temperatures in homes quickly dropped to freezing after heat systems failed, resulting in a public health disaster. After an already trying year, the Food Bank never faltered in its commitment to serve the communities of Southwest Texas.

Because people had no power or water for cooking, operations shifted from grocery deliveries to premade meals. “We never closed,” said Eric. “I had chefs sleeping in the kitchen and working off of a generator.”

Utilizing their stored inventory of food, they started emptying their warehouse to get meals to families, providing food to about 70,000 people the first weekend after the storms. The Food Bank also supplied tens of thousands of meals to the hotels where families were staying after being forced to evacuate their homes. Many of the volunteers who came out to help distribute food, Eric noted, didn’t have power and water in their own houses.

.jpeg)

After delivering potatoes to the San Antonio Food Bank in June 2020, The Farmlink Project has since facilitated deliveries of over 67,000 pounds of mixed greens to the Food Bank in February and March from Taylor Farms in Laredo, Texas.

Despite a tumultuous year, San Antonio Food Bank has responded to crisis after crisis, never wavering from their goal to take a holistic approach to fighting food insecurity and guiding clients to health and self-sufficiency.

“If we’re going to work our way out of the job, it can’t just be about feeding the line. You have to be working to shorten the line,” said Eric. “We fight the daily disaster of poverty, but when a natural disaster occurs, we step up to that too.”

.jpeg)

If you’d like to learn more about San Antonio Food Bank, check out their website here!

If you live in the area and would like to volunteer with the organization, click here.

.png)

.jpeg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)