Tim Bradford has education at the top of his mind. As the Program Coordinator for the Society of Saint Andrew (SoSA) in Jackson, Mississippi, Tim organizes food drops and develops gleaning activities with farmers, serving food insecure communities across the state. Tim also founded and runs the Grower Incentives Program, an organization that encompasses Growers Feeding Families, which he began at the SoSA. The Growers Feeding Families program supports small farmers seeking to grow their operations and diversify their crops. The program provides farmers with vegetable seeds and resources, including educational training, to grow several acres of vegetables like okra, cucumbers, peas, kale, collards, turnips and mustards, alongside their traditional row crops of soybeans and corn. Diversification in the field pads farmers’ incomes, contributes to soil’s long term health, and helps Tim source a variety of fresh vegetables to distribute all over Mississippi. Ultimately, Tim hopes to teach community members, not just farmers, about the value of growing their own food.

Tim’s work is crucial in a state that, from a public health standpoint, suffers from a food insecurity epidemic: Mississippi’s sixteen percent food insecurity rate is roughly four percent higher than the national average. The risk of food insecurity also compounds the risk of mental health problems, obesity, anemia and asthma, according to the United Health Foundation.

Tim sees knowledge about growing food, and having a choice in what one eats, as important to improving individual health. “When people are growing for themselves, they can grow what they like and what’s nutritious for them. Choice and preference are intertwined.” Tim’s observations lend insight into the common critique of food donation programs. While necessary for many counties across the country, donated food often lacks variety and rarely includes fresh produce.

Of course, the question of choice comes back to resource access. State and federal policies are largely responsible for individuals’ access to education and land on which to grow food, in addition to healthcare, job opportunities and other resources necessary for a community’s stability. Tim’s efforts form part of a bottom-up solution to a problem that needs attention from the top-down.

Tim’s upbringing and education have informed his vision for the health of Mississippi. He was raised on his family’s farm in Isola, Mississippi, where he has raised his four sons and still farms today. He studied agronomy, taught for 25 years, and served as the state director of SkillsUSA, an organization that trains high school and college students in technical occupations. Christianity also guides his work. “I love being able to bless people with the products that the growers are blessed to grow,” Tim said. “We believe that if we just follow what the Lord wants us to do, that He’s going to heal our land.”

I let Tim’s words and vision sit with me. Healing the land could help solve many of the health and environmental problems that disproportionately plague Mississippi. Crop diversity supports soil health, helping offset the need for chemicals that contribute to climate change and its effects, prevalent in the state year-round. “We’re used to it,” Tim said of the four to five hurricanes, springtime tornados, and severe floods that Mississippi deals with on a yearly basis.

‘Healing the land,’ more figuratively, speaks to offering people healing, by way of the land. Crop diversity gives people choices of what to eat when policies that perpetuate poverty cycles, especially among African Americans in the rural South, may otherwise limit choices in life. Tim hopes to offer healing by enhancing people’s opportunities to choose—directly from the land.

Healthy land, healthy people. “My greatest vision is not to have a community garden where people can grow among themselves, but to have a community that gardens.” Tim seeks to cultivate a mindset around nutrition, not just a garden. His vision begins with farmers like Shannon Goff of Eubanks Produce, who, as a cohort of Tim’s Grower Incentives Program, has started growing cucumbers alongside his row crops. Last month, Shannon donated four truckloads of cucumbers, which the SoSA distributed to churches and charitable organizations across the state.

Next in Tim’s plans to help diversify Mississippi’s food system? “Fruit trees, nut trees, and the whole nine yards.” We look forward to continuing our collaboration with Tim and SoSA.

< Back

Tim Bradford has education at the top of his mind. As the Program Coordinator for the Society of Saint Andrew (SoSA) in Jackson, Mississippi, Tim organizes food drops and develops gleaning activities with farmers, serving food insecure communities across the state. Tim also founded and runs the Grower Incentives Program, an organization that encompasses Growers Feeding Families, which he began at the SoSA. The Growers Feeding Families program supports small farmers seeking to grow their operations and diversify their crops. The program provides farmers with vegetable seeds and resources, including educational training, to grow several acres of vegetables like okra, cucumbers, peas, kale, collards, turnips and mustards, alongside their traditional row crops of soybeans and corn. Diversification in the field pads farmers’ incomes, contributes to soil’s long term health, and helps Tim source a variety of fresh vegetables to distribute all over Mississippi. Ultimately, Tim hopes to teach community members, not just farmers, about the value of growing their own food.

Tim’s work is crucial in a state that, from a public health standpoint, suffers from a food insecurity epidemic: Mississippi’s sixteen percent food insecurity rate is roughly four percent higher than the national average. The risk of food insecurity also compounds the risk of mental health problems, obesity, anemia and asthma, according to the United Health Foundation.

Tim sees knowledge about growing food, and having a choice in what one eats, as important to improving individual health. “When people are growing for themselves, they can grow what they like and what’s nutritious for them. Choice and preference are intertwined.” Tim’s observations lend insight into the common critique of food donation programs. While necessary for many counties across the country, donated food often lacks variety and rarely includes fresh produce.

Of course, the question of choice comes back to resource access. State and federal policies are largely responsible for individuals’ access to education and land on which to grow food, in addition to healthcare, job opportunities and other resources necessary for a community’s stability. Tim’s efforts form part of a bottom-up solution to a problem that needs attention from the top-down.

Tim’s upbringing and education have informed his vision for the health of Mississippi. He was raised on his family’s farm in Isola, Mississippi, where he has raised his four sons and still farms today. He studied agronomy, taught for 25 years, and served as the state director of SkillsUSA, an organization that trains high school and college students in technical occupations. Christianity also guides his work. “I love being able to bless people with the products that the growers are blessed to grow,” Tim said. “We believe that if we just follow what the Lord wants us to do, that He’s going to heal our land.”

I let Tim’s words and vision sit with me. Healing the land could help solve many of the health and environmental problems that disproportionately plague Mississippi. Crop diversity supports soil health, helping offset the need for chemicals that contribute to climate change and its effects, prevalent in the state year-round. “We’re used to it,” Tim said of the four to five hurricanes, springtime tornados, and severe floods that Mississippi deals with on a yearly basis.

‘Healing the land,’ more figuratively, speaks to offering people healing, by way of the land. Crop diversity gives people choices of what to eat when policies that perpetuate poverty cycles, especially among African Americans in the rural South, may otherwise limit choices in life. Tim hopes to offer healing by enhancing people’s opportunities to choose—directly from the land.

Healthy land, healthy people. “My greatest vision is not to have a community garden where people can grow among themselves, but to have a community that gardens.” Tim seeks to cultivate a mindset around nutrition, not just a garden. His vision begins with farmers like Shannon Goff of Eubanks Produce, who, as a cohort of Tim’s Grower Incentives Program, has started growing cucumbers alongside his row crops. Last month, Shannon donated four truckloads of cucumbers, which the SoSA distributed to churches and charitable organizations across the state.

Next in Tim’s plans to help diversify Mississippi’s food system? “Fruit trees, nut trees, and the whole nine yards.” We look forward to continuing our collaboration with Tim and SoSA.

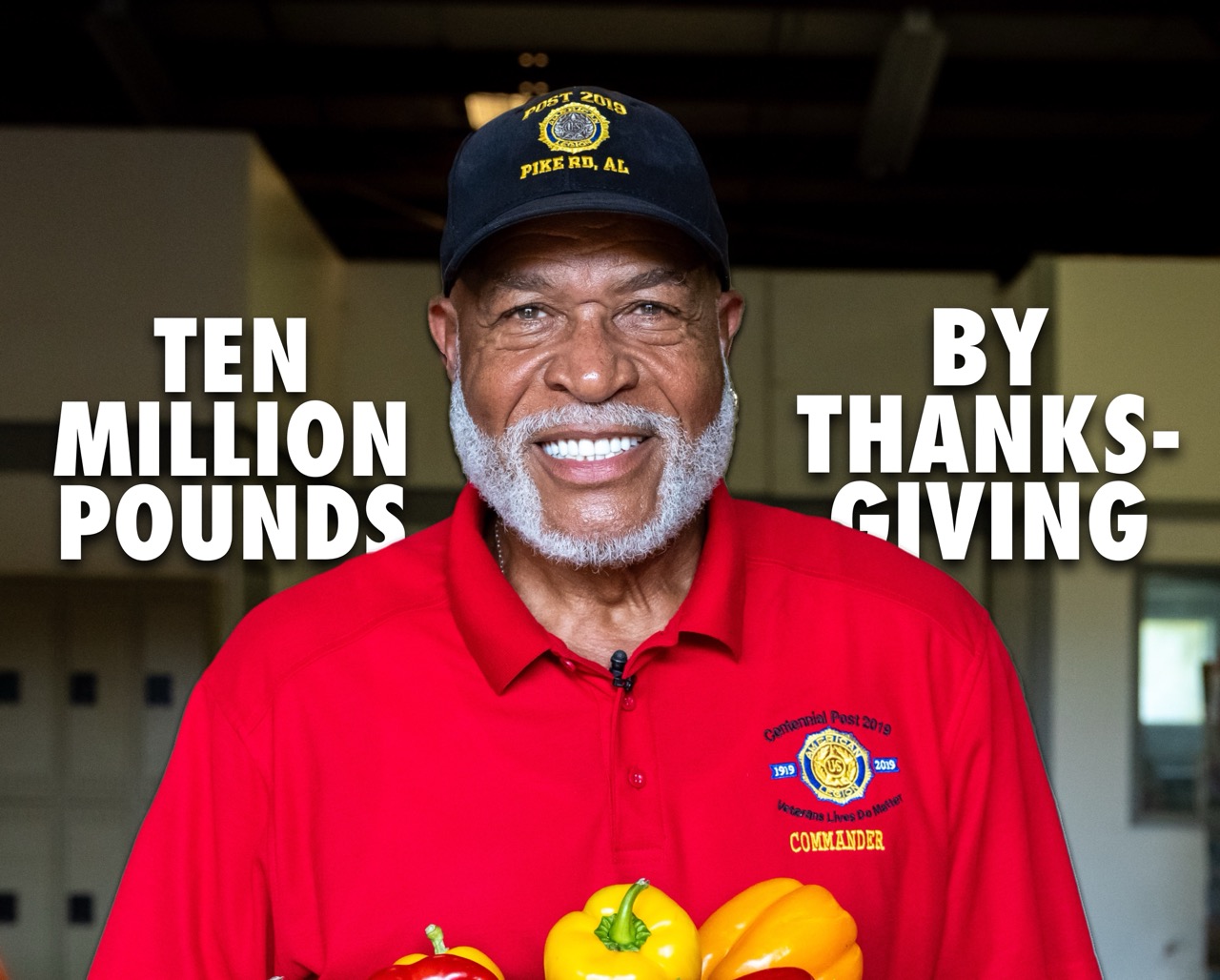

Tim Bradford

Program Coordinator for the Society of Saint Andrew (SoSA)

Tim Bradford has education at the top of his mind. As the Program Coordinator for the Society of Saint Andrew (SoSA) in Jackson, Mississippi, Tim organizes food drops and develops gleaning activities with farmers, serving food insecure communities across the state. Tim also founded and runs the Grower Incentives Program, an organization that encompasses Growers Feeding Families, which he began at the SoSA. The Growers Feeding Families program supports small farmers seeking to grow their operations and diversify their crops. The program provides farmers with vegetable seeds and resources, including educational training, to grow several acres of vegetables like okra, cucumbers, peas, kale, collards, turnips and mustards, alongside their traditional row crops of soybeans and corn. Diversification in the field pads farmers’ incomes, contributes to soil’s long term health, and helps Tim source a variety of fresh vegetables to distribute all over Mississippi. Ultimately, Tim hopes to teach community members, not just farmers, about the value of growing their own food.

Tim’s work is crucial in a state that, from a public health standpoint, suffers from a food insecurity epidemic: Mississippi’s sixteen percent food insecurity rate is roughly four percent higher than the national average. The risk of food insecurity also compounds the risk of mental health problems, obesity, anemia and asthma, according to the United Health Foundation.

Tim sees knowledge about growing food, and having a choice in what one eats, as important to improving individual health. “When people are growing for themselves, they can grow what they like and what’s nutritious for them. Choice and preference are intertwined.” Tim’s observations lend insight into the common critique of food donation programs. While necessary for many counties across the country, donated food often lacks variety and rarely includes fresh produce.

Of course, the question of choice comes back to resource access. State and federal policies are largely responsible for individuals’ access to education and land on which to grow food, in addition to healthcare, job opportunities and other resources necessary for a community’s stability. Tim’s efforts form part of a bottom-up solution to a problem that needs attention from the top-down.

Tim’s upbringing and education have informed his vision for the health of Mississippi. He was raised on his family’s farm in Isola, Mississippi, where he has raised his four sons and still farms today. He studied agronomy, taught for 25 years, and served as the state director of SkillsUSA, an organization that trains high school and college students in technical occupations. Christianity also guides his work. “I love being able to bless people with the products that the growers are blessed to grow,” Tim said. “We believe that if we just follow what the Lord wants us to do, that He’s going to heal our land.”

I let Tim’s words and vision sit with me. Healing the land could help solve many of the health and environmental problems that disproportionately plague Mississippi. Crop diversity supports soil health, helping offset the need for chemicals that contribute to climate change and its effects, prevalent in the state year-round. “We’re used to it,” Tim said of the four to five hurricanes, springtime tornados, and severe floods that Mississippi deals with on a yearly basis.

‘Healing the land,’ more figuratively, speaks to offering people healing, by way of the land. Crop diversity gives people choices of what to eat when policies that perpetuate poverty cycles, especially among African Americans in the rural South, may otherwise limit choices in life. Tim hopes to offer healing by enhancing people’s opportunities to choose—directly from the land.

Healthy land, healthy people. “My greatest vision is not to have a community garden where people can grow among themselves, but to have a community that gardens.” Tim seeks to cultivate a mindset around nutrition, not just a garden. His vision begins with farmers like Shannon Goff of Eubanks Produce, who, as a cohort of Tim’s Grower Incentives Program, has started growing cucumbers alongside his row crops. Last month, Shannon donated four truckloads of cucumbers, which the SoSA distributed to churches and charitable organizations across the state.

Next in Tim’s plans to help diversify Mississippi’s food system? “Fruit trees, nut trees, and the whole nine yards.” We look forward to continuing our collaboration with Tim and SoSA.

.png)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)